教程 - 协程(Coroutine)与通道(Channel)

在这篇教程中, 你将学习如何在 IntelliJ IDEA 中使用协程(Coroutine)执行网络请求, 而不阻塞底层的线程, 也不使用回调.

你将学习:

为什么以及如何使用挂起函数, 执行网络请求.

如何使用协程(Coroutine), 并发的发送请求.

如何使用通道(Channel), 在不同的协程(Coroutine)之间共享信息.

对于网络请求, 你需要使用 Retrofit 库, 但本教程中演示的方法, 对于其他支持协程的库也是适用的.

开始之前的准备步骤

下载并安装 IntelliJ IDEA 的最新版本.

在欢迎界面中选择 Get from VCS, 或选择菜单 File | New | Project from Version Control, clone 项目模板.

你也可以通过命令行 clone:

git clone https://github.com/kotlin-hands-on/intro-coroutines

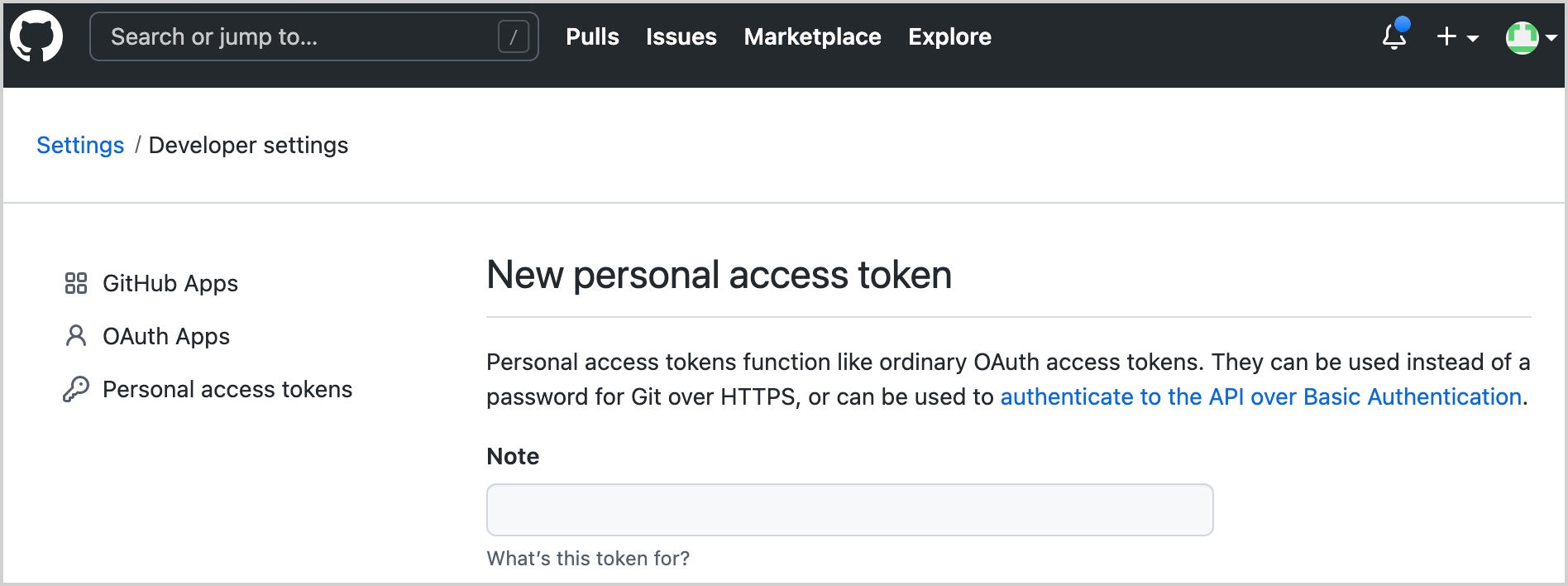

生成一个 GitHub 开发者 token

在你的项目中将会使用 GitHub API. 为了得到访问权限, 请提供你的 GitHub 账户名称, 以及密码或 token. 如果你启用了 two-factor 认证, token 就足够了.

生成一个新的 GitHub token, 以便通过 你的账户 使用 GitHub API:

指定你的 token 名称, 例如,

coroutines-tutorial:

不要指定任何 scope. 点击页面底部的 Generate token.

复制生成的 token.

运行代码

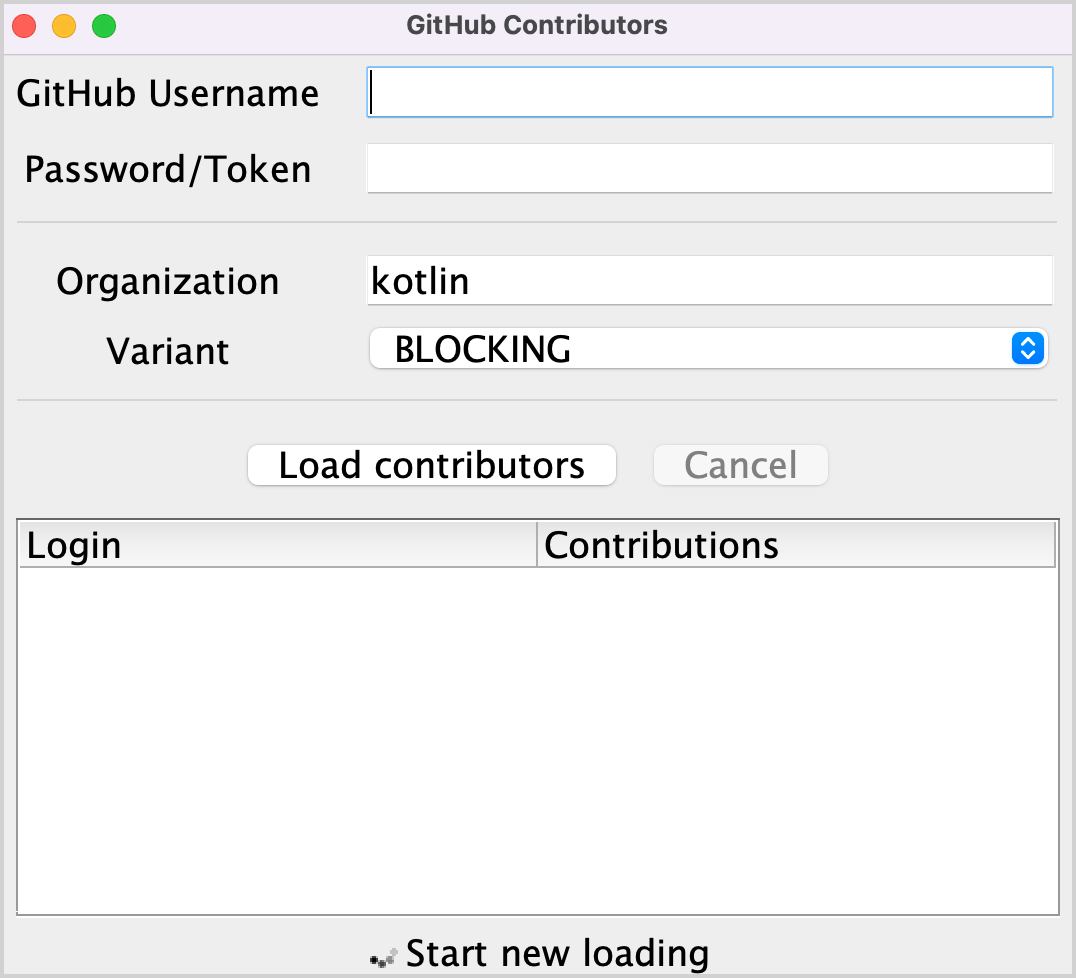

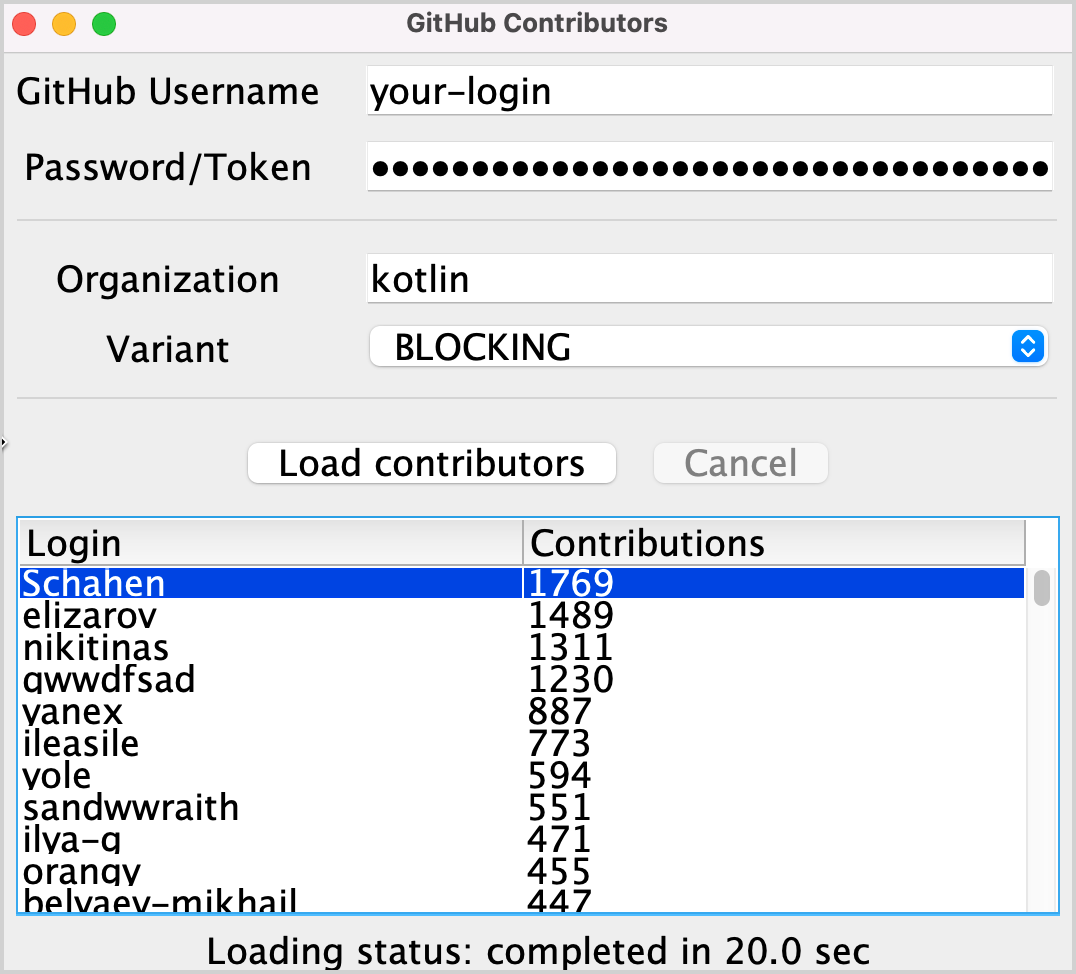

这个程序读取指定的组织之下的 (默认为 "kotlin")之下所有代码仓库的贡献者. 后面你会添加逻辑, 将用户按照他们的贡献数量排序.

打开 the

src/contributors/main.kt文件, 并运行main()函数. 你会看到以下窗口:

如果字体太小, 可以修改

main()函数中setDefaultFontSize(18f)的值来调整字体大小.在对应的输入框中填写你的 GitHub 用户名和 token (或密码).

确定在 Variant 下拉菜单中选择了 BLOCKING.

点击 Load contributors. UI 会冻结一段时间, 然后显示贡献者列表.

打开程序的输出, 确认数据已加载. 每次请求成功后, 贡献者列表会输出到日志.

有不同的方法来实现这个逻辑: 可以使用 阻塞请求(Blocking Request), 或者使用 回调(Callback). 你将会比较这些解决方案和使用 协程(Coroutine) 的方案, 了解如何使用 通道 在不同的协程之间共享信息.

阻塞请求(Blocking Request)

你将使用 Retrofit 库执行对 GitHub 的 HTTP 请求. 它允许获取指定的组织之下的代码仓库的列表, 以及代码仓库的贡献者列表:

loadContributorsBlocking() 函数使用这个 API 来获取指定组织的贡献者列表.

请打开

src/tasks/Request1Blocking.kt, 查看它的实现:fun loadContributorsBlocking( service: GitHubService, req: RequestData ): List<User> { val repos = service .getOrgReposCall(req.org) // #1 .execute() // #2 .also { logRepos(req, it) } // #3 .body() ?: emptyList() // #4 return repos.flatMap { repo -> service .getRepoContributorsCall(req.org, repo.name) // #1 .execute() // #2 .also { logUsers(repo, it) } // #3 .bodyList() // #4 }.aggregate() }首先, 得到指定组织下的代码仓库列表, 保存到

reposlist 中. 然后, 对每个代码仓库, 请求贡献者列表, 并将所有列表合并为最终的贡献者列表.getOrgReposCall()和getRepoContributorsCall()都返回*Call类 (#1处) 的实例. 这个时刻, 还没有发送请求.然后调用

*Call.execute(), 执行请求 (#2处).execute()是一个同步调用, 会阻塞底层的线程.得到应答时, 调用

logRepos()和logUsers()函数, 将结果输出到日志 (#3处). 如果 HTTP 应答包含错误, 错误也会在这里输出到日志.最后, 得到应答的 body 部, 其中包含你需要的数据. 对本教程来说, 如果发生错误, 会使用空的列表作为结果结果 , 并将对应的错误输出到日志 (

#4处).

为了避免重复

.body() ?: emptyList()这样的代码, 声明了扩展函数bodyList():fun <T> Response<List<T>>.bodyList(): List<T> { return body() ?: emptyList() }再次运行程序, 看看 IntelliJ IDEA 中的系统输出. 应该类似以下内容:

1770 [AWT-EventQueue-0] INFO Contributors - kotlin: loaded 40 repos 2025 [AWT-EventQueue-0] INFO Contributors - kotlin-examples: loaded 23 contributors 2229 [AWT-EventQueue-0] INFO Contributors - kotlin-koans: loaded 45 contributors ...每行的第一项, 是程序启动之后经过的毫秒数, 之后是线程名称, 包含在方括号中. 你可以看到获取数据的请求是从哪个线程调用的.

每行的最后一项是实际的消息: 获取了多少个代码仓库或贡献者.

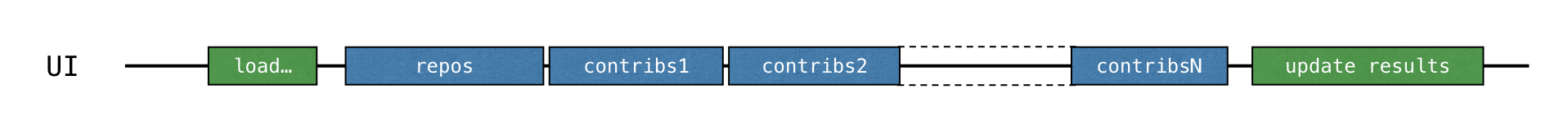

这个日志输出演示了, 所有的结果都是从主线程输出的. 当你使用 BLOCKING 选项运行代码时, 窗口会冻结, 不能对输入作出反应, 直到数据加载结束. 所有的请求, 都会从与调用

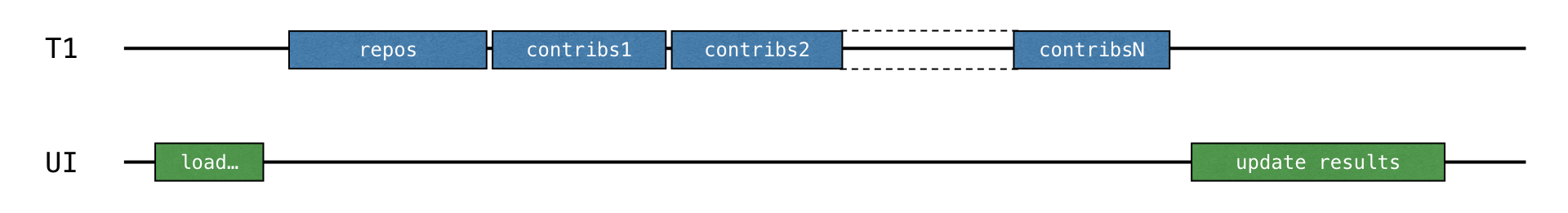

loadContributorsBlocking()的相同线程执行, 这个线程就是 UI 主线程 (在 Swing 中, 它是一个 AWT 事件派发线程). 这个主线程会被阻塞, 所以 UI 会冻结:

在贡献者列表加载完成后, 会更新结果.

在

src/contributors/Contributors.kt中, 找到loadContributors()函数, 它负责选择如何加载贡献者, 看看它如何调用loadContributorsBlocking():when (getSelectedVariant()) { BLOCKING -> { // 阻塞 UI 线程 val users = loadContributorsBlocking(service, req) updateResults(users, startTime) } }updateResults()调用紧跟在loadContributorsBlocking()调用之后.updateResults()更新 UI, 因此始终必须从 UI 线程调用它.由于

loadContributorsBlocking()也是从 UI 线程调用的, 因此 UI 线程会被阻塞, UI 会冻结.

任务 1

第 1 个任务帮助你熟悉任务内容. 现在, 每个贡献者的名字重复了多次, 他们参与的每个项目都出现了他们的名字. 请实现 aggregate() 函数, 合并用户, 让每个贡献者只添加一次. User.contributions 属性应该包含指定的用户对 所有 项目的贡献总数. 结果列表应该根据贡献数量降序排列.

打开 src/tasks/Aggregation.kt, 实现 List<User>.aggregate() 函数. 用户应该按照他们的贡献总数排序.

对应的测试文件 test/tasks/AggregationKtTest.kt 展示了期待的结果的例子.

完成这个任务之后, "kotlin" 组织的结果列表应该类似以下内容:

任务 1 的解答

要按照 login 名称对用户分组, 请使用

groupBy(), 它返回一个 map, key 为 login 名称, value 为这个 login 名称的用户在各个代码仓库中的出现情况.对每个 map entry, 计算每个用户的贡献总数, 并根据指定的名称和贡献总数, 创建

User类的一个新实例.对结果列表按照降序排序:

fun List<User>.aggregate(): List<User> = groupBy { it.login } .map { (login, group) -> User(login, group.sumOf { it.contributions }) } .sortedByDescending { it.contributions }

另一种解决方案是使用 groupingBy() 函数, 而不是 groupBy().

回调(Callback)

前面的解答能够正确工作, 但它会阻塞线程, 因此冻结了 UI. 避免这个问题的一个传统方法是 使用 回调(Callback).

不必在操作完成之后立即调用代码, 你可以将它抽取为一个单独的回调, 通常是一个 Lambda 表达式, 并将这个 Lambda 表达式传递给调用者, 以便以后调用它.

为了让 UI 保持响应, 你可以将整个计算过程移动到单独的线程中, 或者将 Retrofit API 切换为使用回调, 而不是使用阻塞调用.

使用背景线程

请打开

src/tasks/Request2Background.kt, 查看它的实现. 首先, 整个计算过程移动到了一个不同的线程.thread()函数启动一个新的线程:thread { loadContributorsBlocking(service, req) }现在, 整个加载被移动到了一个单独的线程, 主线程成为空闲, 能够处理其他任务:

loadContributorsBackground()函数的签名变了. 它接受一个updateResults()回调作为它的最后一个参数, 以便在所有的加载过程完成之后调用它:fun loadContributorsBackground( service: GitHubService, req: RequestData, updateResults: (List<User>) -> Unit )现在, 在调用

loadContributorsBackground()时,updateResults()调用会在回调内进行, 而不是像以前那样立即调用:loadContributorsBackground(service, req) { users -> SwingUtilities.invokeLater { updateResults(users, startTime) } }通过调用

SwingUtilities.invokeLater, 你可以确保更新结果的updateResults()调用, 发生在主 UI 线程 (AWT 的事件派发线程) 上.

但是, 如果你尝试使用 BACKGROUND 选项加载贡献者 , 你会看到列表被更新, 但没有任何变化.

任务 2

修正 src/tasks/Request2Background.kt 中的 loadContributorsBackground() 函数, 让结果列表显示在 UI 中.

任务 2 的解答

如果你尝试加载贡献者, 你可以看到日志输出, 显示贡献者已被加载, 但结果没有显示. 为了解决这个问题, 请对结果的用户列表调用 updateResults():

要确保明确的调用通过回调传入的代码逻辑. 否则, 什么都不会发生.

使用 Retrofit 的回调 API

在前面的解决方案中, 整个加载逻辑移动到了背景线程中, 但这仍然没有达到对资源的最佳利用. 所有的加载请求都是顺序执行的, 在等待加载结果时线程会被阻塞, 但它其实可以用来执行其他任务. 具体来说, 线程可以开始加载另一个请求, 这样就能更快的得到整个结果.

对每个代码仓库的数据处理应该分为两个部分: 加载, 以及处理应答结果. 第 2 个 处理 部分应该抽取到一个回调中.

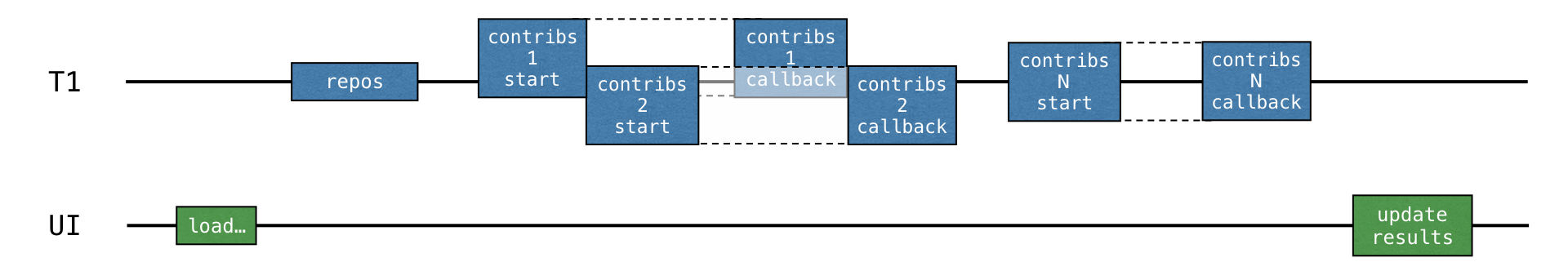

这样, 对每个代码仓库的加载可以在收到前一个代码仓库的结果(以及调用对应的回调)之前开始:

Retrofit 回调 API 能够帮助你实现这一点. Call.enqueue() 函数启动一个 HTTP 请求, 并接受一个回调作为参数. 在这个回调中, 你需要指定在每个请求之后进行什么处理.

请打开 src/tasks/Request3Callbacks.kt, 查看 loadContributorsCallbacks() 的实现, 它使用这个 API:

为了方便, 这段代码使用了同一个文件中声明的

onResponse()扩展函数. 它接受一个 Lambda 表达式作为参数, 而不是一个对象表达式.应答处理逻辑被抽取到回调中: 对应的 Lambda 表达式在

#1和#2处启动.

但是, 提供的解决方案不能正确工作. 如果你运行程序, 并选择 CALLBACKS 选项来加载贡献者, 你会看到没有显示任何数据. 但是, Request3CallbacksKtTest 中的测试立即返回结果, 表示它已经成功通过测试.

请思考为什么这段代码不能按预期工作, 尝试修正它, 或者请查看下面的解答.

任务 3 (可选)

重写 src/tasks/Request3Callbacks.kt 文件中的代码, 让加载的贡献者列表能够显示.

任务 3 的解答, 第一次尝试

在目前的解决方案中, 并发的启动了很多请求, 这样减少了总的加载时间. 但是, 结果没有加载. 这是因为 updateResults() 回调是在所有的加载请求启动之后立即被调用, 这是在 allUsers 列表填充数据之前.

你可以通过以下修正, 尝试修正这个问题:

首先, 使用索引遍历代码仓库列表 (

#1处).然后, 对每个回调, 检查它是不是最后一次迭代 (

#2处).如果是, 更新结果.

但是, 这段代码也不能达成我们的目标. 请尝试自己找到答案, 或者查看下面的解答.

任务 3 的解答, 第二次尝试

由于加载请求是并发启动的, 因此无法保证最后一次请求的结果会最后收到. 结果的顺序可能是任意的.

因此, 如果你用当前迭代序号与 lastIndex 比较, 作为结束的条件, 那么会有失去某些代码仓库的结果的风险.

如果处理最后一个代码仓库的请求, 比之前的某个请求更快返回 (这是很可能发生的), 执行时间更长的所有请求, 结果都会丢失.

解决这个问题的一种方法是, 引入一个序号, 检查是否已经处理了所有的代码仓库:

这段代码使用同步版本的列表和 AtomicInteger(), 这是因为, 一般来说不能保证处理 getRepoContributors() 请求的各个回调总是在相同的线程中调用.

任务 3 的解答, 第三次尝试

更好的解决方案是使用 CountDownLatch 类. 它保存一个计数器, 初始值是代码仓库数量. 这个计数器在处理每个代码仓库之后递减一次. 等待计数器递减到 0, 然后更新结果:

然后结果在主线程中更新. 这样比将逻辑委托给子线程更加直接.

在回顾解答的这三次尝试之后, 你可以看到, 编写正确的回调代码并不简单, 而且容易出错, 尤其是出现多个底层线程和同步的情况.

挂起函数(Suspending Function)

你可以使用挂起函数(Suspending Function)实现相同的逻辑. 不要返回 Call<List<Repo>>, 而是将 API 调用定义为一个 挂起函数, 如下:

getOrgRepos()定义为suspend函数. 当你使用一个挂起函数来执行一个请求时, 底层线程不会被阻塞. 关于它的工作原理, 详情会在后面的小节中介绍.getOrgRepos()直接返回结果, 而不是返回一个Call. 如果结果不成功, 会抛出一个异常.

或者, Retrofit 允许返回封装在 Response 内的结果. 这种情况下, 会提供结果的 body 部, 可以手动检查错误. 本教程使用返回 Response 的版本.

请在 src/contributors/GitHubService.kt 中, 向 GitHubService 接口添加以下声明:

任务 4

你的任务是修改加载贡献者的函数代码, 让它使用两个新的挂起函数, getOrgRepos() 和 getRepoContributors(). 新的 loadContributorsSuspend() 函数会被标记为 suspend, 以便使用新的 API.

将

src/tasks/Request1Blocking.kt中定义的loadContributorsBlocking()的实现, 复制到src/tasks/Request4Suspend.kt中定义的loadContributorsSuspend()内.修改代码, 让它使用新的挂起函数, 而不是使用返回

Call的函数.选择 SUSPEND 选项运行程序, 确认在执行 GitHub 请求时 UI 仍然保持响应.

任务 4 的解答

将 .getOrgReposCall(req.org).execute() 替换为 .getOrgRepos(req.org), 对第 2 个 "contributors" 请求也进行同样的替换:

loadContributorsSuspend()应该定义为suspend函数.你不再需要调用

execute, 之前由它返回Response, 因为现在 API 函数直接返回Response. 注意, 这个细节只适用于 Retrofit 库. 使用其它库时, API 会不同, 但概念是一样的.

协程(Coroutine)

这段使用挂起函数的代码看起来与 "阻塞" 版本类似. 与阻塞版本的主要区别是, 它不会阻塞线程, 而是挂起协程(Coroutine):

启动一个新的协程

如果你查看在 src/contributors/Contributors.kt 如何使用 loadContributorsSuspend(), 你会看到它在 launch 之内调用. launch 是一个库函数, 它接受一个 Lambda 表达式作为参数:

这里, launch 启动一个新的计算过程, 负责加载数据和显示结果. 计算过程是可挂起的 – 在执行网络请求时, 它会被挂起, 并释放底层的线程. 当网络请求返回结果时, 计算过程会恢复执行.

这样的可挂起的计算过程被称为一个 协程(Coroutine). 因此, 在这个示例中, launch 启动了一个新的协程, 负责加载数据和显示结果.

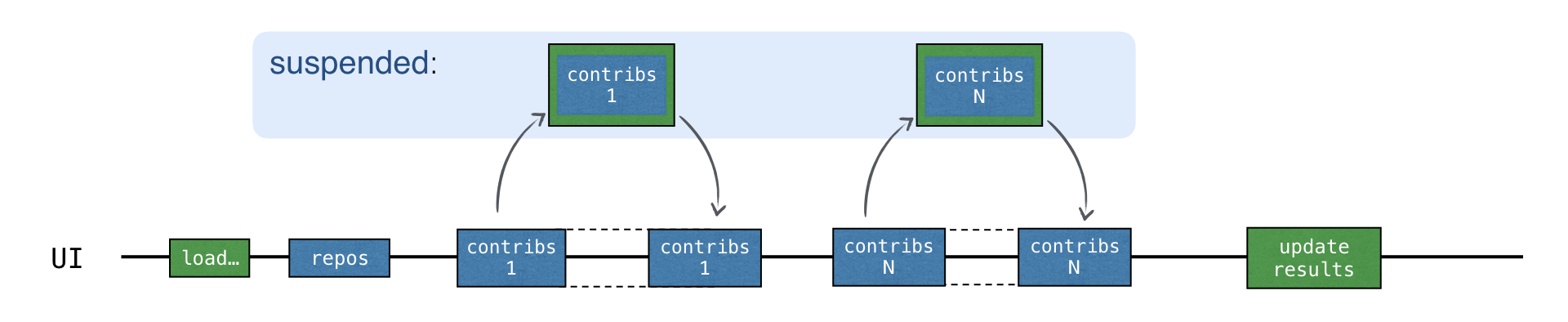

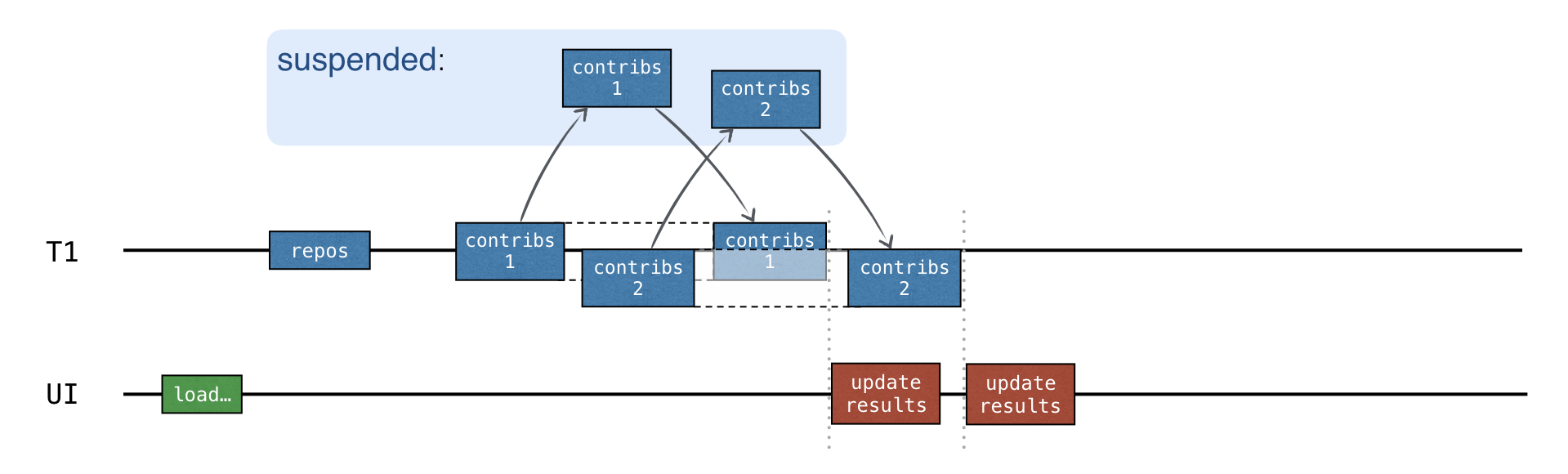

协程在线程上运行, 而且可以挂起. 当一个协程挂起时, 对应的计算过程会暂停, 从线程中删除, 保存在内存中. 此时, 线程可以供其它任务使用:

当计算过程准备好继续执行时, 它会返回到一个线程中 (不一定是同一个线程).

在 loadContributorsSuspend() 示例中, 每个 "contributors" 请求现在会使用挂起机制等待结果. 首先, 会发送新的请求. 然后, 在等待应答时, 由 launch 函数启动的整个 "load contributors" 协程会被挂起.

直到收到对应的应答之后, 协程才会恢复:

在等待应答时, 线程可以执行其它任务. 尽管所有的请求都发生在主 UI 线程上, 但 UI 仍然保持响应:

使用 SUSPEND 选项运行程序. log 表明所有的请求都是从主 UI 线程发送的:

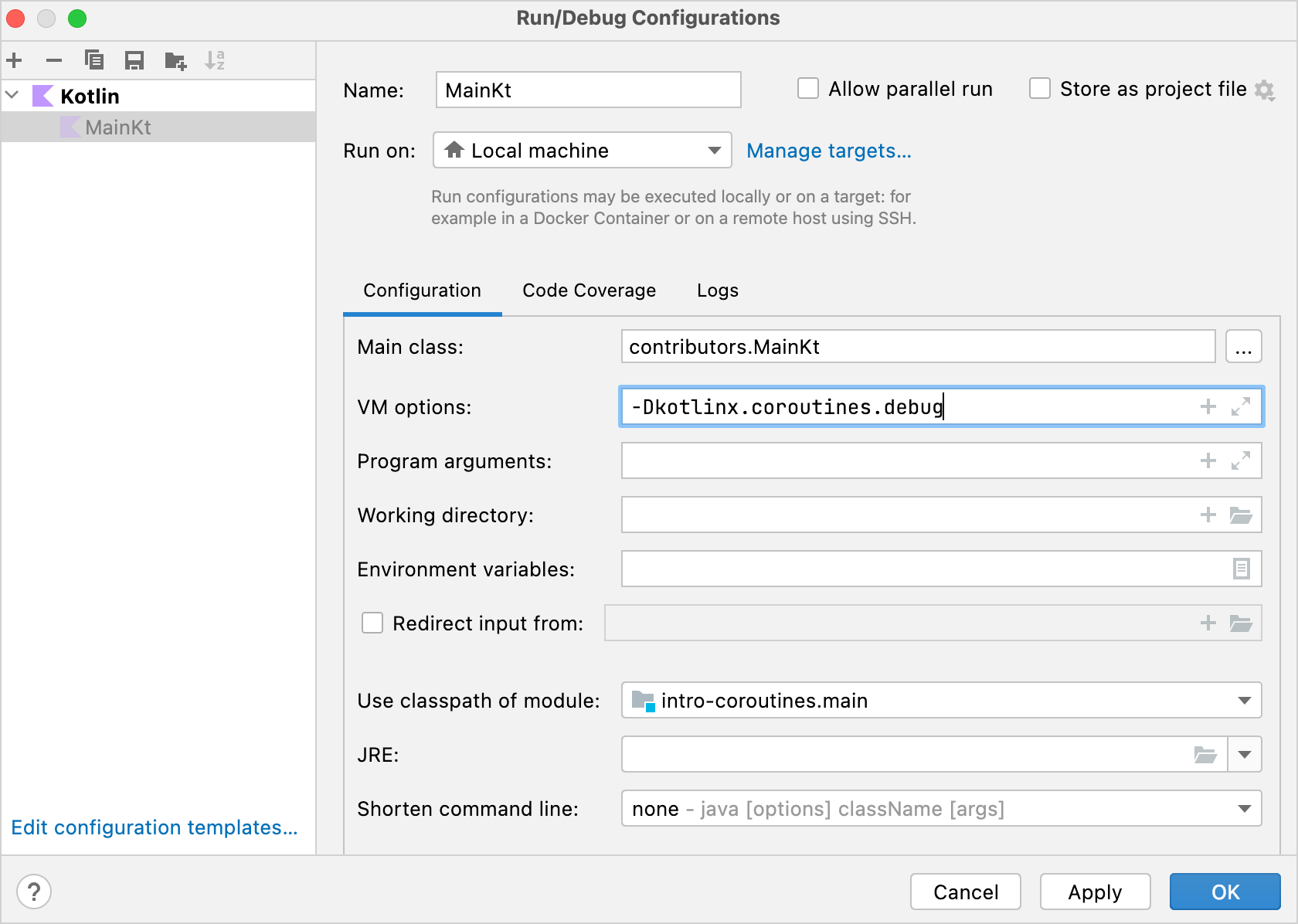

2538 [AWT-EventQueue-0 @coroutine#1] INFO Contributors - kotlin: loaded 30 repos 2729 [AWT-EventQueue-0 @coroutine#1] INFO Contributors - ts2kt: loaded 11 contributors 3029 [AWT-EventQueue-0 @coroutine#1] INFO Contributors - kotlin-koans: loaded 45 contributors ... 11252 [AWT-EventQueue-0 @coroutine#1] INFO Contributors - kotlin-coroutines-workshop: loaded 1 contributorslog 能够向你显示对应的代码运行在哪个协程上. 要启用这个功能, 请打开 Run | Edit configurations, 添加

-Dkotlinx.coroutines.debugVM 选项:

当

main()使用这个选项运行时, 协程名称会添加在线程名称之后. 你也可以修改运行所有 Kotlin 文件的模板, 默认启用这个选项.

现在所有的代码运行在一个协程上, 也就是上面提到的 "load contributors" 协程, 标记为 @coroutine#1. 在等待结果时, 你不应该重用线程来发送另一个请求, 因为这段代码是顺序编写的. 直到前一个结果收到之后, 新的请求才会发送.

挂起函数平等的对待线程, 不会阻塞线程来进行 "等待". 但是, 这种方案仍然没有实现任何并发.

并发

Kotlin 协程占用的资源比线程要少得多. 每次你想要启动一个新的异步计算过程, 你都可以创建一个新的协程.

要启动新的协程, 请使用几个主要的 协程构建器 之一: launch, async, 或 runBlocking. 不同的库也可能定义额外的协程构建器.

async 启动一个新的协程, 并返回一个 Deferred 对象. Deferred 表达的概念也叫做 Future 或 Promise. 它保存一个计算过程, 但它 推迟(Defer) 你得到最终结果的时刻; 它 承诺(Promise) 在 未来(Future) 的某个时刻给出结果.

async 和 launch 的主要区别是, launch 用来启动一个计算过程, 并不期待返回具体的结果. launch 返回一个 Job, 表示协程. 可以调用 Job.join(), 等待它运行结束.

Deferred 是一个泛型类型, 继承自 Job. 一个 async 调用可以返回一个 Deferred<Int> 或一个 Deferred<CustomType>, 具体取决于 Lambda 表达式返回什么结果 (Lambda 表达式内的最后一个表达式就是结果).

要得到一个协程的结果, 你可以对 Deferred 实例调用 await(). 在等待结果时, 调用这个 await() 的协程会被挂起:

runBlocking 用作通常的函数与挂起函数之间的桥梁, 或者说阻塞与非阻塞世界之间的桥梁. 它充当一个适配器, 用来启动顶级的主协程. 它应该主要用在 main() 函数和测试中.

如果有一组 Deferred 对象的列表, 你可以调用 awaitAll(), 等待所有这些对象的结果:

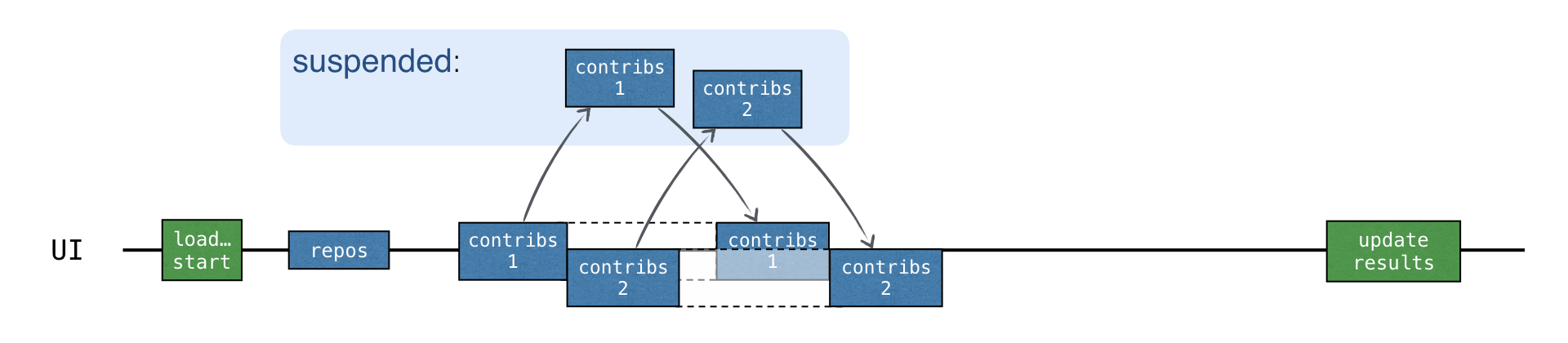

当每个 "contributors" 请求都在一个新的协程中启动时, 所有的请求都是异步启动的. 可以在收到前一个请求的结果之前发送新的请求:

总的加载时间与 CALLBACKS 版本大致一样, 但不需要任何回调. 此外, async 明确的强调了代码中的哪些部分是并发运行的.

任务 5

在 Request5Concurrent.kt 文件中, 使用前面的 loadContributorsSuspend() 函数, 实现一个 loadContributorsConcurrent() 函数.

任务 5 的提示

你只能在一个协程的作用范围(Scope)内启动一个新的协程. 请将 loadContributorsSuspend() 的内容复制到 coroutineScope 调用中, 以便能够调用 async 函数:

你的解答应该基于以下架构:

任务 5 的解答

使用 async 封装每个 "contributors" 请求, 创建与代码仓库数量相同的协程. async 返回 Deferred<List<User>>. 这不会造成问题, 因为创建新的协程不会消耗太多资源, 因此你可以根据需要, 创建任意多的协程.

你不能再使用

flatMap, 因为map结果现在是一个Deferred对象的列表, 而不是列表的列表.awaitAll()返回List<List<User>>, 因此要调用flatten().aggregate()来得到结果:suspend fun loadContributorsConcurrent( service: GitHubService, req: RequestData ): List<User> = coroutineScope { val repos = service .getOrgRepos(req.org) .also { logRepos(req, it) } .bodyList() val deferreds: List<Deferred<List<User>>> = repos.map { repo -> async { service.getRepoContributors(req.org, repo.name) .also { logUsers(repo, it) } .bodyList() } } deferreds.awaitAll().flatten().aggregate() }运行代码, 并检查日志. 所有的协程仍然在主 main UI 线程上运行, 因为还没有使用多线程, 但你已经能够看到并发运行协程的好处了.

要修改这段代码, 在共通线程池的不同线程上运行 "contributors" 协程, 请对

async函数的 context 参数指定Dispatchers.Default:async(Dispatchers.Default) { }CoroutineDispatcher决定对应的协程应该运行在哪个或哪些线程上. 如果不指定参数,async会使用外层作用范围(Scope)的派发器.Dispatchers.Default表示 JVM 上的共用线程池. 这个池提供了一种并行执行的方法. 它包含与 CPU 核数量一样多的线程, 但如果只有 1 个 CPU 核, 它仍然会包含 2 个线程.

修改

loadContributorsConcurrent()函数中的代码, 在共通线程池的不同线程上启动新的协程. 此外, 在发送请求前添加额外的日志:async(Dispatchers.Default) { log("starting loading for ${repo.name}") service.getRepoContributors(req.org, repo.name) .also { logUsers(repo, it) } .bodyList() }再次运行程序. 在日志中, 你可以看到各个协程可以在线程池的一个线程上启动, 并在另一个线程上恢复运行:

1946 [DefaultDispatcher-worker-2 @coroutine#4] INFO Contributors - starting loading for kotlin-koans 1946 [DefaultDispatcher-worker-3 @coroutine#5] INFO Contributors - starting loading for dokka 1946 [DefaultDispatcher-worker-1 @coroutine#3] INFO Contributors - starting loading for ts2kt ... 2178 [DefaultDispatcher-worker-1 @coroutine#4] INFO Contributors - kotlin-koans: loaded 45 contributors 2569 [DefaultDispatcher-worker-1 @coroutine#5] INFO Contributors - dokka: loaded 36 contributors 2821 [DefaultDispatcher-worker-2 @coroutine#3] INFO Contributors - ts2kt: loaded 11 contributors例如, 在这段日志中,

coroutine#4在worker-2线程上启动, 在worker-1线程上继续运行.

在 src/contributors/Contributors.kt 中, 查看 CONCURRENT 选项的实现:

要只在主 UI 线程上运行协程, 请将参数指定为

Dispatchers.Main:launch(Dispatchers.Main) { updateResults() }如果在主线程上启动新的协程时主线程正在繁忙, 那么协程会被挂起, 并被调度为在这个线程上执行. 直到线程空闲时, 协程才会恢复运行.

好的做法是使用外层作用范围的派发器, 而不是在每个端点明确指定. 如果你定义

loadContributorsConcurrent(), 而不传入Dispatchers.Default作为参数, 你就可以在任何上下文中调用这个函数: 使用Default派发器, 使用主 UI 线程, 或使用自定义的派发器.后面你会看到, 在测试中调用

loadContributorsConcurrent()时, 你可以使用TestDispatcher调用它, 这样可以简化测试. 这就使得这个解决方案更加灵活.

要在调用端指定派发器, 请对项目进行进行以下修改, 让

loadContributorsConcurrent在继承的上下文中启动协程:launch(Dispatchers.Default) { val users = loadContributorsConcurrent(service, req) withContext(Dispatchers.Main) { updateResults(users, startTime) } }updateResults()应该在主 UI 线程上调用, 因此你使用Dispatchers.Main调用它.withContext()使用指定的协程上下文调用指定的代码, 它会挂起直到代码执行完成, 并返回结果. 表达这一点的另一种方法是(但更加麻烦), 启动一个新的协程, 并明确的等待(通过挂起), 直到执行完成:launch(context) { ... }.join().

运行代码, 确认协程在线程池的线程上执行.

结构化并发

协程的作用范围(Scope) 负责管理不同协程之间的结构和父-子 关系. 新的协程通常需要在一个作用范围之内启动.

协程上下文(Context) 保存用来运行一个特定协程的附加技术信息, 例如协程的自定义名称, 或指定协程应该调度到哪个线程之上的派发器.

当使用 launch, async, 或 runBlocking 来启动一个新的协程时, 它们会自动创建对应的作用范围. 所有这些函数都接受一个带接受者的 Lambda 表达式作为参数, CoroutineScope 是隐含的接受者类型:

新的协程只能在一个作用范围之内启动.

launch和async被声明为CoroutineScope的扩展函数, 因此调用它们时, 必须传递隐含的或显式的接受者.由

runBlocking启动的协程是唯一的例外, 因为runBlocking定义为顶级函数. 但由于它阻塞当前线程, 因此它主要用在main()函数和测试中, 作为桥梁函数.

runBlocking, launch, 或 async 内的新协程, 会自动在作用范围之内启动:

当你在 runBlocking 之内调用 launch 时, 它会作为隐含的 CoroutineScope 类型接受者的扩展函数来调用. 或者, 你可以明确的写为 this.launch.

嵌套的协程 (在这个示例中由 launch 启动) 可以看作外层协程 (由 runBlocking 启动) 的子协程. 这种 "父-子" 关系通过作用范围实现; 子协程会从父协程对应的作用范围启动.

使用 coroutineScope 函数, 可以创建一个新的作用范围而不启动新的协程. 要在 suspend 函数之内以结构化的方式启动新的协程, 而不访问外层作用范围, 你可以创建 一个新的协程作用范围, 它自动成为调用这个 suspend 函数的外层作用范围的子作用范围. loadContributorsConcurrent() 是一个很好的例子.

你也可以使用 GlobalScope.async 或 GlobalScope.launch, 从全局作用范围启动一个新的协程. 这样会创建一个顶级的 "独立" 协程.

协程结构背后的机制称为 结构化并发. 与全局作用范围相比, 它提供了以下优点:

作用范围通常负责子协程, 子协程的生存周期与作用范围的生存周期相关联.

如果发生某种问题, 或者用户改变想法, 决定撤销操作, 作用范围可以自动取消子协程.

作用范围自动等待所有子协程执行完成. 因此, 如果作用范围对应于一个协程, 父协程直到其作用范围之内启动的所有协程都执行完成之后, 才会执行完成.

使用 GlobalScope.async 时, 将几个协程绑定到较小的作用范围的结构. 从全局作用范围启动的协程都是独立的 – 它们的生存周期只受整个应用程序的生存周期的限制. 可以保存一个从全局作用范围启动的协程的引用, 等待它执行完成, 或者明确的取消它, 但这些操作不会像结构化并发那样自动进行.

取消加载贡献者

创建加载贡献者列表的函数的两个版本. 比较一下, 当你想要取消父协程时这两个版本的行为有什么不同. 第一个版本使用 coroutineScope 启动所有子协程, 第二个版本使用 GlobalScope.

在

Request5Concurrent.kt中, 向loadContributorsConcurrent()函数添加 3 秒延迟:suspend fun loadContributorsConcurrent( service: GitHubService, req: RequestData ): List<User> = coroutineScope { // ... async { log("starting loading for ${repo.name}") delay(3000) // 加载代码仓库的贡献者 } // ... }这个延迟会影响发送请求的所有协程, 因此在协程启动之后, 但在请求发送之前, 有足够的时间来取消加载.

创建加载函数的第二个版本: 将

loadContributorsConcurrent()的实现复制到Request5NotCancellable.kt中的loadContributorsNotCancellable(), 然后删除新的coroutineScope的创建.async调用现在会无法解析, 因此使用GlobalScope.async来启动它们:suspend fun loadContributorsNotCancellable( service: GitHubService, req: RequestData ): List<User> { // #1 // ... GlobalScope.async { // #2 log("starting loading for ${repo.name}") // 加载代码仓库的贡献者 } // ... return deferreds.awaitAll().flatten().aggregate() // #3 }函数现在直接返回结果, 而不是作为 Lambda 表达式内的最后一个表达式 (

#1处和#3处).所有的 "contributors" 协程在

GlobalScope内启动, 而不是作为协程作用范围的子范围(#2).

运行程序, 并选择 CONCURRENT 选项来加载贡献者.

等待所有的 "contributors" 协程启动, 然后点击 Cancel. 日志显示没有新的结果, 这就意味着所有的请求都确实被取消了:

2896 [AWT-EventQueue-0 @coroutine#1] INFO Contributors - kotlin: loaded 40 repos 2901 [DefaultDispatcher-worker-2 @coroutine#4] INFO Contributors - starting loading for kotlin-koans ... 2909 [DefaultDispatcher-worker-5 @coroutine#36] INFO Contributors - starting loading for mpp-example /* click on 'cancel' */ /* no requests are sent */重复第 5 步, 但这一次选择

NOT_CANCELLABLE选项:2570 [AWT-EventQueue-0 @coroutine#1] INFO Contributors - kotlin: loaded 30 repos 2579 [DefaultDispatcher-worker-1 @coroutine#4] INFO Contributors - starting loading for kotlin-koans ... 2586 [DefaultDispatcher-worker-6 @coroutine#36] INFO Contributors - starting loading for mpp-example /* click on 'cancel' */ /* but all the requests are still sent: */ 6402 [DefaultDispatcher-worker-5 @coroutine#4] INFO Contributors - kotlin-koans: loaded 45 contributors ... 9555 [DefaultDispatcher-worker-8 @coroutine#36] INFO Contributors - mpp-example: loaded 8 contributors这时, 没有协程被取消, 所有的请求仍然发送了.

查看在 "contributors" 程序中取消是如何触发的. 当 Cancel 按钮被点击时, 主 "loading" 协程被明确的取消, 子协程则自动被取消:

interface Contributors { fun loadContributors() { // ... when (getSelectedVariant()) { CONCURRENT -> { launch { val users = loadContributorsConcurrent(service, req) updateResults(users, startTime) }.setUpCancellation() // #1 } } } private fun Job.setUpCancellation() { val loadingJob = this // #2 // 如果 'cancel' 按钮被点击, 取消加载任务: val listener = ActionListener { loadingJob.cancel() // #3 updateLoadingStatus(CANCELED) } // 向 'cancel' 按钮添加监听器: addCancelListener(listener) // 在加载任务完成后, 更新状态, 并删除监听器 } }

launch 函数返回一个 Job 实例. Job 保存 "loading 协程" 的一个引用, 这个协程加载所有数据, 并更新结果. 你可以对它调用 setUpCancellation() 扩展函数(#1 处), 传递 Job 的一个实例作为接受者.

另一种表达方式是明确的写:

为了提高可读性, 在

setUpCancellation()函数内, 可以使用新的loadingJob变量引用函数的接受者(#2处).然后可以向 Cancel 按钮添加监听器, 使得当它被点击时, 取消

loadingJob(#3处).

使用结构化并发, 你只需要取消父协程, 这样会将取消自动的传播到所有的子协程.

使用外层作用范围的上下文(Context)

在指定的作用范围内启动新的协程, 可以更容易的确保所有协程都使用相同的上下文(Context)运行. 如果需要, 也可以更容易的替换上下文(Context).

现在是时候学习使用外层作用范围的派发器是如何工作的了. 由 coroutineScope 或由协程构建器创建的新的作用范围, 总是会继承外层作用范围的上下文. 这里, 外层作用范围就是调用 suspend loadContributorsConcurrent() 函数的作用范围:

所有的嵌套协程自动使用继承的上下文启动. 派发器是这个上下文的一部分. 这就是为什么由 async 启动的所有协程, 都使用默认派发器的上下文来启动:

使用结构化并发, 你可以在创建顶级协程时, 一次性指定主要的上下文元素 (例如派发器). 然后, 所有的嵌套协程都会继承上下文, 只在需要的时候修改.

显示进度

尽管某些代码仓库的信息加载非常快, 但只有在所有数据加载完毕后, 用户才能看到结果列表. 在此之前, 加载图标会显示进度, 但没有关于当前状态的信息, 也没有已经加载的贡献者信息.

你可以提前显示中间结果, 并在对每个代码仓库加载数据之后, 显示所有的贡献者:

要实现这个功能, 在 src/tasks/Request6Progress.kt 中, 你需要以回调的方式, 传递更新 UI 的逻辑, 以便对每个中间状态调用它:

在 Contributors.kt 中的调用端, 对于 PROGRESS 选项, 传递了回调, 以便从 Main 线程更新结果:

在

loadContributorsProgress()中,updateResults()参数声明为suspend. 在对应的 Lambda 表达式参数中, 需要调用withContext, 它是一个suspend函数.updateResults()回调接受一个额外的 Boolean 参数, 表示加载是否已经完成, 结果是不是最终结果.

任务 6

在 Request6Progress.kt 文件中, 实现 loadContributorsProgress() 函数, 它显示中间进度. 请以 Request4Suspend.kt 的 loadContributorsSuspend() 函数为基础.

使用一个没有并发的简单版本; 你会在下一节中添加并发.

贡献者的中间列表应该以 "聚合" 状态显示, 而不仅仅是从每个代码仓库加载的用户列表.

每个新的代码仓库的数据加载之后, 每个用户的贡献总数应该增加.

任务 6 的解答

为了以 "聚合" 状态保存已加载贡献者的中间列表, 定义一个 allUsers 变量, 它保存用户列表, 然后在每个新的代码仓库的贡献者加载之后, 更新它:

连续 vs 并发

每个请求完成之后, 会调用一次 updateResults() 回调:

这段代码不包含并发. 它是顺序执行的, 因此你不需要同步.

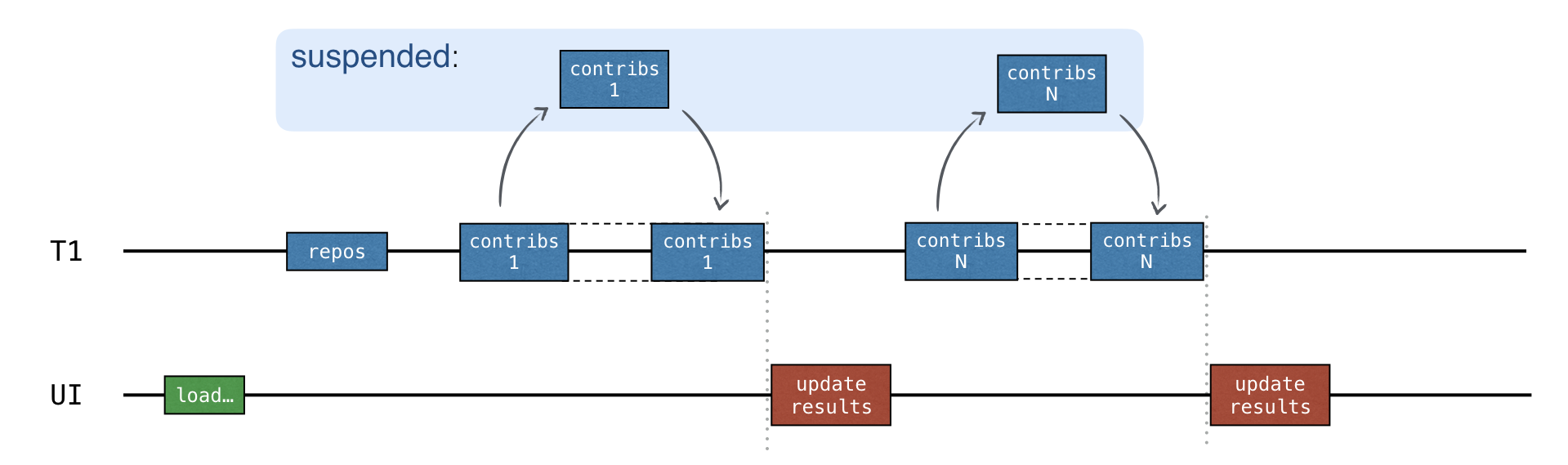

最好的选择是, 并发的发送请求, 并在得到每个代码仓库应答之后, 更新中间结果:

为了添加并发功能, 请使用 通道(Channel).

通道(Channel)

编写包含共用的可变状态的代码是非常困难的, 而且易于出错 (就像在使用回调的解决方案中一样). 更简单的方法是通过通信来共享信息, 而不是使用共通的可变状态. 协程可以通过 通道(Channel) 相互通信.

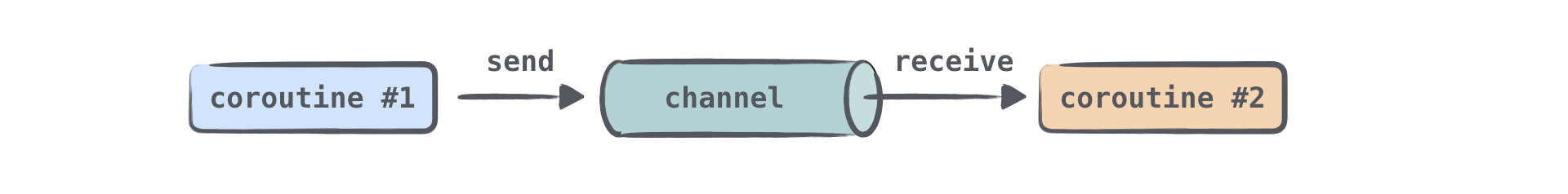

通道是一种通信原语, 允许数据在协程之间传递. 一个协程可以向一个通道(Channel) 发送 一些信息, 另一个协程可以从通道 接受 这个信息:

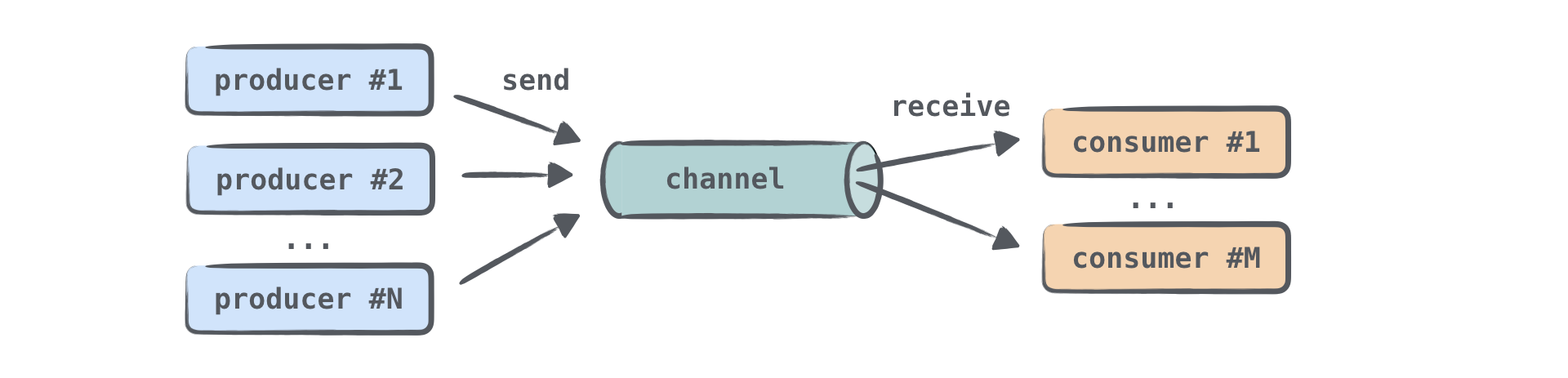

发送 (生产) 信息的协程通常称为生产者(Producer), 接受 (消费) 信息的协程通常称为消费者(Consumer). 一个或多个协程可以向同一个通道发送信息, 一个或多个协程可以从通道接受数据:

当多个协程从同一个通道接受信息时, 每个元素只被其中一个消费者处理一次. 一旦一个元素被处理, 它就会立即从通道中删除.

你可以将通道看作类似于元素的集合, 或者更准确的说, 一个队列(Queue), 元素在一端添加, 在另一端接受. 但是, 存在重要的区别: 不同于集合, 即使是同步版本的集合, 通道可以 挂起 send() 和 receive() 操作. 当通道空, 或满时, 就会发生这样的情况. 如果通道大小有上限, 通道就可能会满.

Channel 由 3 个不同的接口表示: SendChannel, ReceiveChannel, 和 Channel, 最后一个接口继承前两个接口. 你通常会创建一个通道, 并将它作为 SendChannel 实例提供给生产者, 这样就只有生产者能够向通道发送信息. 你将通道作为 ReceiveChannel 实例提供给消费者, 这样就只有消费者能够从通道接受信息. send 和 receive 方法都声明为 suspend:

生产者能够关闭通道, 表示不会再有新的元素到来.

库中定义了几种类型的通道. 它们的区别在于, 内部能够保存的元素数量, 以及 send() 调用是否能够挂起. 对于所有通道的类型, receive() 调用的行为都是类似的: 如果通道不空, 它接受一个元素; 否则, 它会挂起.

- 无限(Unlimited)通道

无限(Unlimited)通道与队列(Queue)最近似: 生产者能够向这个通道发送元素, 通道则会无限制的增长.

send()调用永远不会阻塞. 如果程序耗尽内存, 你会遇到OutOfMemoryException. 无限通道与队列之间的区别是, 当消费者企图从空的通道接受数据时, 它会被挂起, 直到某个新元素被发送到通道.

- 缓冲(Buffered)通道

缓冲(Buffered)通道的大小限制为指定的值. 生产者能够向这个通道发送元素, 直到达到大小限制. 所有元素在内部保存. 当通道满时, 对它进行的下一个

send()调用会被挂起, 直到出现更多的可用空间.

- 约会(Rendezvous)通道

"约会(Rendezvous)" 通道是一个没有缓冲区的通道, 等于一个缓冲大小为 0 的缓冲通道. 其中一个函数 (

send()或receive()) 总是会被挂起, 直到另一个函数被调用.如果

send()函数被调用, 而且不存在挂起的receive()调用准备处理元素, 那么send()会被挂起. 类似的, 如果receive()函数被调用, 而且通道为空, 或者说, 不存在 挂起的send()调用准备发送元素, 那么receive()调用会被挂起."约会(Rendezvous)" 这个名字 ("在约定的时间和地点会面") 表示的意思是,

send()和receive()应该在 "同一时间会合".

- 合并(Conflated)通道

发送到合并(Conflated)通道的新元素会覆盖之前发送的元素, 因此接受者始终只会得到最新的元素.

send()调用 永远不会挂起.

当你创建通道时, 要指定它的类型, 或缓冲区大小 (你需要的是缓冲通道的话):

默认情况下, 会创建 "约会(Rendezvous)" 通道.

在下面的任务中, 你将创建一个 "约会" 通道, 两个生产者协程, 以及以及消费者协程:

任务 7

在 src/tasks/Request7Channels.kt 中, 实现函数 loadContributorsChannels(), 它并发的请求所有的 GitHub 贡献者, 同时显示中间进度.

使用之前的函数, Request5Concurrent.kt 中的 loadContributorsConcurrent(), 以及 Request6Progress.kt 中的 loadContributorsProgress().

任务 7 的提示

并发的从不同的代码仓库接受贡献者列表的不同的协程, 可以将接受到的所有结果发送到同一个通道:

然后可以从这个通道逐个的接受元素, 并处理:

由于 receive() 调用是顺序的, 因此不需要额外的同步.

任务 7 的解答

和 loadContributorsProgress() 函数一样, 你可以创建一个 allUsers 变量来保存 "all contributors" 列表的中间状态. 从通道接受的每个新列表添加到所有用户的列表. 你可以汇总结果, 并使用 updateResults 回调更新状态:

在得到不同代码仓库的结果之后立即添加到通道. 最初, 当所有请求都发送后, 并且还没有收到数据时,

receive()调用会被挂起. 这时, 整个 "load contributors" 协程 会被挂起.之后, 当用户列表发送到通道时, "load contributors" 协程恢复运行,

receive()调用返回这个列表, 结果立即被更新.

现在你可以运行程序, 并选择 CHANNELS 选项来加载贡献者, 并查看结果.

尽管协程和通道都不能完全消除由并发带来的复杂性, 但当你需要了解具体如何进行时, 它们能让你的任务更加容易一些.

测试协程

我们现在来测试所有的解答, 看看使用并发协程的方案是否比使用 suspend 函数的方案更快, 并检查使用通道的方案是否比使用简单的 "进度" 的方案更快.

在下面的任务中, 你将比较各个方案的总运行时间. 你将模拟一个 GitHub 服务, 让这个服务在指定的超时时间之后返回结果:

使用 suspend 函数的顺序方案会消耗大约 4000 ms (4000 = 1000 + (1000 + 1200 + 800)). 并发方案会消耗大约 2200 ms (2200 = 1000 + max(1000, 1200, 800)).

对于显示进度的方案, 你也可以使用时间戳检查中间结果.

对应的测试数据定义在 test/contributors/testData.kt 中, Request4SuspendKtTest, Request7ChannelsKtTest 等文件包含使用模拟服务调用的直接测试.

但是, 还存在两个问题:

这些测试的运行时间太长. 每个测试消耗 2 到 4 秒, 每次都需要等待结果. 这样效率很低.

你不能依赖各个解答运行的确切时间, 因为仍然需要额外的时间来准备并运行代码. 你可以添加一个常数, 但这样在不同的机器上时间就会不同. 模拟服务的延迟应该高于这个常数, 让你能够看到差异. 如果常数是 0.5 秒, 那么将延迟设置为 0.1 秒就是不够的.

更好的方法是使用特殊的框架, 将相同的代码运行多次, 来测试时间(这样会让总的时间进一步增加), 但这样会难于学习和设置.

为了解决这些问题, 确保使用指定的测试延迟的解答能够按照预期运行, 一个比另一个更快, 请使用 虚拟 时间和一个特殊的测试派发器. 这个派发器追踪启动时传入的虚拟时间, 并在真实时间中立即运行所有操作. 当你使用这个派发器运行协程时, delay 会立即返回, 并让虚拟时间向前推进.

使用这个机制的测试运行很快, 但你仍然能够检查在虚拟时间中不同时刻发生的情况. 总的运行时间会大幅减少:

要使用虚拟时间, 请将 runBlocking 调用替换为 runTest. runTest 接受一个 TestScope 上的扩展 Lambda 表达式作为参数. 在这个特殊的作用范围内, 当你在 suspend 函数中调用 delay 时, delay 会增加虚拟时间, 而不是在真实时间中延迟:

你可以使用 TestScope 的 currentTime 属性, 检查目前的虚拟时间.

这个示例中的总运行时间是几个毫秒, 而虚拟时间等于延迟参数, 也就是 1000 毫秒.

为了在子协程中充分利用 "虚拟" delay 的效果, 请使用 TestDispatcher 启动所有子协程. 否则, 它将不能正确工作. 除非你提供不同的派发器, 否则这个派发器自动从其它 TestScope 继承:

在上面的示例中, 如果使用 Dispatchers.Default 的上下文来调用 launch, 测试会失败. 你会遇到一个异常, 提示任务还没有完成.

只有在 loadContributorsConcurrent() 函数使用继承的上下文启动子协程时, 你才可以通过这样的方式测试它, 而不必修改它, 使用 Dispatchers.Default 派发器.

你可以在 调用 一个函数而不是在 定义 时, 指定上下文元素, 例如派发器, 这样可以提供更高的灵活性, 而且更容易测试.

默认情况下, 如果你使用实验性的测试 API, 编译器会提示警告信息. 为了压制这些警告, 请使用 @OptIn(ExperimentalCoroutinesApi::class) 标注测试函数, 或包含测试的整个类. 添加编译器参数, 指示编译器, 你在使用实验性 API:

在本教程对应的项目中, Gradle 脚本已经添加了编译器参数.

任务 8

重构 tests/tasks/ 中的以下测试, 使用虚拟时间而不是真实时间:

Request4SuspendKtTest.ktRequest5ConcurrentKtTest.ktRequest6ProgressKtTest.ktRequest7ChannelsKtTest.kt

比较重构之前与之后的总运行时间.

任务 8 的提示

将

runBlocking调用替换为runTest, 将System.currentTimeMillis()替换为currentTime:@Test fun test() = runTest { val startTime = currentTime // 执行动作 val totalTime = currentTime - startTime // 测试结果 }对检查确切虚拟时间的断言, 取消注释.

不要忘记添加

@UseExperimental(ExperimentalCoroutinesApi::class).

任务 8 的解答

下面是并发和通道的 test case 的答案:

首先, 检查是否在预期的虚拟时间内得到结果, 然后检查结果本身是否正确:

对于使用通道的最终版本, 第一个中间结果要比 progress 版本更快得到, 你可以在测试中使用虚拟时间看到差异.

下一步做什么

查看 KotlinConf 上的 使用 Kotlin 进行异步编程 研讨会.

了解关于使用 虚拟时间和实验性的测试包 的更多详情.